|

| The Vampire of Barcelona |

While surfing the Internet, looking for some photographs for

a project dealing with the Spanish Civil War, I came upon a photograph of a

grim-faced woman, which happened to be juxtaposed with pictures of children

killed in bombing raids during the war. Dark haired, heavy browed, with what

looked like pockmarks on her forehead, she appeared to radiate malice. Curious,

I pursued the picture and Googled the name of its subject, one Enriqueta Martí

Ripolles, and found accounts of a ghastly story that dated to a century ago. According to various websites,

Enriqueta (her name would be Henrietta in English) Martí had a career that

combined the worst elements of Jack the Ripper, Hannibal Lecter, the Wicked

Stepmother in Snow White, panderer for pedophiles, and that rare prototype, the

Female Serial Killer.

All

of this took place in Barcelona during the first decade or so of the 20th

century, ending with spectacularly gruesome revelations in 1912 in connection

with the kidnapping of a five-year-old girl named Teresita Guitart. The story took place in a slum in

Barcelona called the Raval, which enjoyed a reputation about as evil as Hell’s

Kitchen in New York or Whitechapel in London at that time.

Here

is the sensational story as it was recounted in the contemporary Yellow

Journalist Press with all of its macabre frills, bells and whistles:

Teresa

Guitart had been missing for several weeks; the child wandered off while her

mother was talking with a friend in the neighborhood, and disappeared. Searches turned up nothing, until, a

woman who lived on what was then called Ponent Street looked up at a

second-floor window and saw a child she had never seen in the neighborhood, who

appeared to be waving at her.

Almost immediately, the window’s shutters were snapped shut. She saw the same face at a back window

shortly thereafter, with the window again swiftly shuttered. Her suspicions aroused, she and a

friend called the police, who eventually checked out the apartment. It was most dirty, smelly and dark, and

there they found two little girls, one of which turned out to be little

Teresita. They arrested the adult

who lived there, Enriqueta Martí, and were soon able to reunite Teresita with

her parents.

According

to the press, most notably the daily newspaper La Vanguardia, investigation of Martí began to reveal a singularly

gruesome history. It was said that

inside the dirty and messy apartment, the police found some children’s clothing

of rich materials, as well as a large, bloodstained butcher knife. Amidst all the squalor, they also found

one richly appointed room, papered scarlet, with elegant furniture of a similar

color (shades of Shades of Gray!).

Further searches revealed small bones, and other apartments that Enriqueta

rented concealed more. There were

also books and papers, lists of names, and other writings in unintelligible

scripts.

|

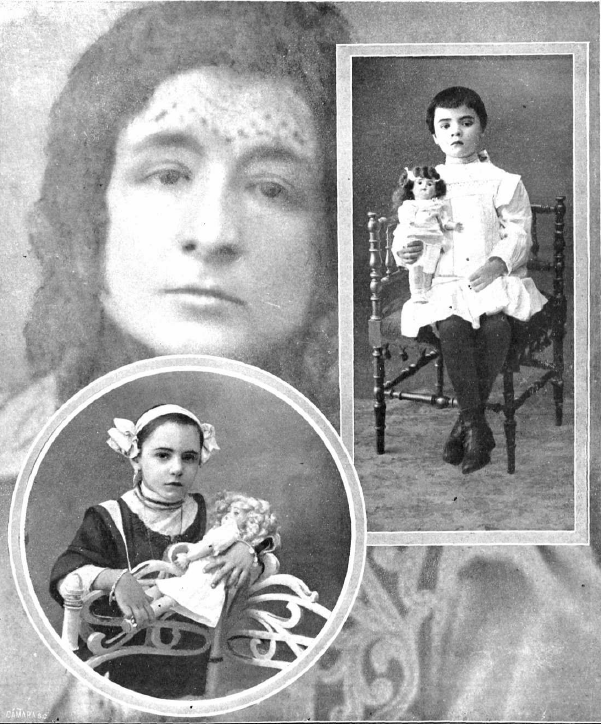

| Antoni Esplugas's montage of Enriqueta, Angelita and Teresita |

The other child, named Angelita,

who Enriqueta claimed was her daughter, was not her child at all. Witnesses now

recounted that Enriqueta had often been seen with Angelita, or another child,

wearing rags, begging in the street, not only in the Raval, but in wealthier

districts too. Then came rumors

that Enriqueta also appeared at night, richly dressed, in fashionable spots

such as the Liceu Opera House and upscale gambling casinos.

But wait! There was more!

Angelita had told authorities (or was it reporters?) that a little boy,

named Pepito, had also lived with herself and Enriquita before Teresita’s

arrival, and that she had witnessed Enriqueta murder him (presumably with the

butcher knife) in her kitchen. And

then came the most lurid accusation: Enriqueta not only kidnapped little

children, even babes in arms, but also grabbed street orphans. Some of them she used on her begging

outings. Worse, many of them had

been offered to rich upper class pedophiles to be made use of in that hidden

scarlet room. And inconceivably

worse still, after these children were used, she butchered them, using their

belly fat, bone marrow, hair and blood to make creams and unguents that she

then sold to upper class patrons for treatments against tuberculosis, STDs, and

as anti-aging creams. Finally, she

was even said to drink their blood to revive her own energies, thus earning her

the title of “The Vampire of Barcelona.”

Other allegations swirled around

her: that she herself had been a prostitute, that she had performed abortions,

that she was abused, aided and abetted by her father, and had a stormy

relationship with her husband, Juan Pujaló, a failed artist, and God knows what

else.

It did turn out that Enriqueta had

a police record; in 1909 she had been arrested for pimping child prostitutes,

but had been able to avoid punishment, presumably because she had an

influential patron. In a flurry, parents who had lost children came out of the

woodwork, accusing Enriqueta of abducting them. Rumors flew about those lists of names from the apartment,

darkly suggesting that they were client lists for services and products, and

included some of the most powerful people in the city, who naturally wanted

everything hushed up, and the list, of course, conveniently disappeared.

Nor did the tale end with the

lady’s imprisonment. She was reputed

to have attempted suicide and had to be constrained by force; and that eventually

she was lynched by fellow inmates, grossed out by her deeds, in the prison

courtyard.

The scholar in me can recommend

some of the more lurid accounts in the contemporary Barcelona Newspaper La Vanguardia, particularly in articles

from February 28 through the first week of March of 1912, or the pamphlet La secuestradora de niños, ( una vida de crímenes), by Guillermo Nuñez de Prado, who

managed to write and publish it, with a lurid cover, by May of that year. The full-blown urban legend as it

survives today can be found on several websites to be found at the end of this

blogpost, replete with pictures of alleged child victims, actually casualties

of the Spanish Civil War 25 years later.

What intrigued me about Enriqueta

Martí Ripollés was that all the details I was reading created the mother legend

of evilness and perversity. She

was Snow White’s Wicked Stepmother, beautiful when she wanted to be, hag when

it suited her. She was a

combination of Hannibal Lecter and Ilse Koch, drinking the blood of children

and processing their remains into saleable beauty product, chopping them up for

these purposes with the clinical precision of Jack the Ripper. She was every mother’s nightmare:

abductor and killer of children.

She was Queen of Conspiracies, protected by wealthy and corrupt

politicians, who were also her customers, because she also had incriminating

lists—blackmailers and blackmailees. She was the Evil Uppity Woman: Vampire,

Witch, Hag and Corrupter of Innocence, a Misogynist’s dream.

And international! Her misdeeds, further garbled, even

made the newspapers of small-town America. For example, an article appeared in

the Oswego [New York] Daily Times on October 19,1912 under the

headline

SIX-TIME MURDERESS ESCAPES GALLOWS. Killed Children and

Made Alleged Love Philtres from Blood:

“Enriqueta Marti,

the woman who kidnapped six or more children, murdered them and made alleged

love philtres from their blood, was sentenced to eleven months in prison. A small fine was also imposed.

Cables reaching

New York from Barcelona last March stated that Barcelona was greatly agitated

over the disappearance of several children. The police arrested a woman named Enriqueta Marti, aged 50,

who although married was childless.

Investigation

showed that the woman, with a number of accomplices, kidnapped the children and

later murdered them, using the infantile blood for love philters.

One infant was

rescued from the house of the woman and the remains of another was found in the

woman’s former residence. The

little girl who was rescued was called Angelita and she said that one time she

was made to eat the flesh of a child who had perished a short time before.”

The problem is, of course that she

wasn’t all that. Within a short amount of time, investigators determined that

the bones found on her various premises were not human, but animal, and that a

number of them, not surprisingly in a badly-built slum, probably trapped

between gaping parts of the structures, the others proved to be chicken and

other meat bones, probably used for cooking. If Enriqueta had lived today, DNA evidence and other

forensic tools would probably have discounted many of the more lurid

rumors—which probably would have not even been circulated in the first place.

It appears also that Enriqueta died in prison, not of assassination, but, as

her obituary declared, of uterine cancer at age 45.

In recent years, efforts towards a

more balanced portrait of Enriqueta have appeared. The Spanish historian and

novelist Elsa Plaza has researched Enriqueta’s case and used her as a character

in her recent novel, El Cielo Bajo los

Pies (2011), and has done a great deal to clarify her case, particularly in

terms of feminist analysis of disadvantaged women in Spain at the beginning of

the 20th century, as has Catalina Gayá in an article also published

in 2011 in El Periódico de Barcelona.

And just last year, the Catalan journalist Jordi Corominas, published Barcelona 1912: El Caso de Enriqueta Martí,

which deals with the popular press of the era and its treatment of Martí. A

good summary of all this can be found in an article by Ivan Vila in the periodical

El Punt Avui.

So the creams and “philters” were

doubtless a figment of an overheated imagination, and the scarlet room was too,

and there’s no solid evidence that she ever murdered anyone—not even little

Pepito, who turned out to be alive after all.

And even Teresita’s family wasn’t

adverse to a little exploitation; the whole family appeared later on the local

vaudeville stage as celebrities.

Not that she was just a blameless,

disadvantaged woman, victimized by a misogynist all-male press either. Given her earlier arrest, she probably

was a procuress of children over at least a decade, bad and unpalatable enough,

like many before her, and certainly, beyond the wishful thinking of Internet

child pornography, still going on.

But the urban Black Legend won’t

die, as the numerous websites dealing with her attest. The dead children from

the Civil War still turn up attached to her life and career. A

thriller-detective novel by Marc Pastor, called Barcelona Shadows appeared in 2006, reveals her in all her sinister

glory—and a murderess too.

As I write this, Enriqueta’s

residence on what was 29 Ponent Street (since renamed Joaquim Costa Street) can

be seen in tours of the sinister side of Barcelona, and you can even buy the

T-shirt!

|

| The T-Shirt |

Even the photograph on Wikipedia

that I had first seen in my Google search, when compared with other

reproductions posted elsewhere, seems to make her worse than she was (those

pockmarks are clearly part of a black transparent veil). And the cover of Nuñez

de Prado’s book is a Grimm’s Fairy Tale gone berzerk

|

| The book cover |

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Some Sources for the Urban Legend of Enriqueta Martí

Marc Pastor’s scenery-chewing Enriqueta is found in his novel, Barcelona Shadows, translated into English by Mara Faye Lethem, and published by Pushkin Press in 2006

Elsa Plaza’s novel, El

Cielo Bajo los Pies, was published in 2011 by Edhasa. It is available at Amazon.com.

Catalina Gayá’s article

I”El miserio de siempre” in El Diario de

Barcelona (Dec. 4, 2011

Jordi Corominas’s book, Barcelona

1912: El Caso de Enriqueta Martí, was published by Silex in 2014. Its cover has a kinder, gentler Enriqueta:

Marc Pastor’s scenery-chewing Enriqueta is found in his

novel, Barcelona Shadows, translated

into English by Mara Faye Lethem, and published by Pushkin Press in 2006

_________________________________________

The Urban Legend can be found at numerous sites on the Internet; just google! Here's a sample

There are also plenty in English

Judy, this was a great read - do some more!

ReplyDeleteCarolee, I fully intend to; next up (sooner or later), several blogs on Goya's Avatar.

DeleteThose "pockmarks" on her forehead are actually part of a black lace veil. It shows up in better resolutions of the same photograph.

ReplyDelete