Take a look at your basic art history survey textbook, and it will often have a title called HISTORY OF WESTERN ART or some variation thereof. Back in the late 1950’s when I was an undergraduate student, my professor for this course was H. W. Janson, who wrote one of the original gold-standard books on this topic. In those days, WESTERN ART meant about five or six countries of western Europe: Italy, France, Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands, and generally in the timeframe ending with Impressionism, or maybe even Cubism. Other countries, like ancient Greece, Rome, Egypt, and Mesopotamia, Romanesque and 16th-17th Spain, and a few other places at a few moments in history were included. This canon, basically designated by European scholars, museum curators and art aficionados covered the “major arts” of painting, sculpture and architecture, primarily limited to religious and court art, with a nod to Dutch 17th century bourgeoisie. Key works of art were discussed individually, generally authenticated or attributed, analyzed and praised or damned in relation to the canon. Renaissance Italy and the 17th century Netherlands seemed to have been regarded as the pinnacles.

At Harvard, where I got my Ph.D, anybody like me, with an interest in late Medieval Spain was considered a loony outlander, a lover of inferior provincials, left to myself in my madness. It was only in the later 20th century and now in the 21st, that the discipline of Art History has changed, widened, and effectively now includes old and new visual imagery all over the world, in diverse media and diverse intent. The line between “commercial” and “fine” art has virtually dissolved, and changed our viewpoint of what “fine” art is, since until the 18th century, all “fine” art was basically commercial anyway, and most of what is preserved is skewed towards what had been preserved in churches and palaces of the rich, the more common stuff relegated to mere archeology or “decorative arts” or “popular arts,” of no aesthetic consequence.

In the United States, and especially for those living west of the Mississippi. “Western Art” can have a completely different meaning. Here it means art of the American West and encompasses American and western themed art and objects. You can think of “Cowboys and Indians,” but it spans and includes much more, from imagery done by early visitors from the early 19th century, through landscapes, portraits, works and objects chronicling 19th-century westward expansion, to both interpretations of 20th-21st century life in the west, and a large body of realistic painting and sculpture that preserves the dream of native Americans, the pioneer and frontier life. It also encompasses what in the old days would have been called “minor arts, but they’re hardly that: elaborate saddles, swords, firearms spurs and other accoutrements also qualify. It is a vast field, as broad as the regional differences through time and space of the west itself, and there are more than a dozen museums devoted to it.

During the last fifty years or so, serious art historians have been applying themselves to it, particularly to its 19th-century manifestations. For a blog entry, it is way too large to discuss this Western Art as a whole, so as an art historian here I wanted to look at only one work each of two contemporary painters that are now on exhibit at the Briscoe Museum in San Antonio, both part of a show lent from the Booth Museum in Atlanta entitled “Into a New West.” I have chosen them because the painters themselves generously gave me permission to reproduce them, but primarily also because I can apply some of the criteria connected with the old parameters put forth from that earlier HISTORY OF WESTERN ART tradition. Both artists have some training and experience in graphic design as well as gallery pieces, but their styles, subject matter, and manner of narration are very different though both are set in the American southwest.

|

| Michael Goettee: Red Rocks Romance, Booth Western Art Museum Permanent Collection, Cartersville, GA |

|

| Nardo di Cione Madonna and saints, Washington, National Gallery |

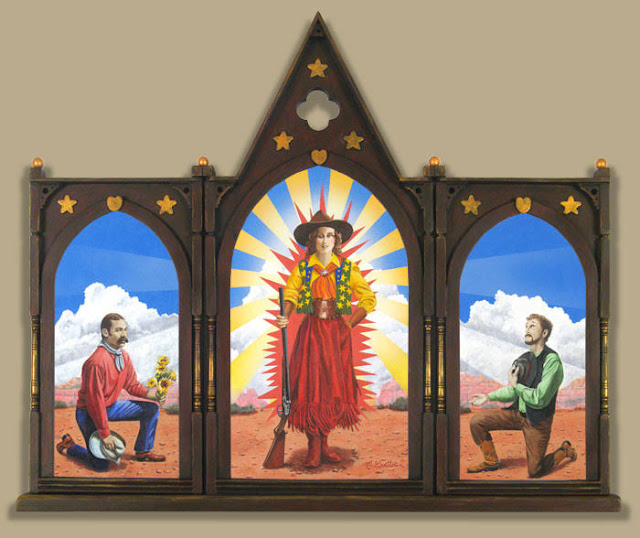

The first piece is Michael Goettee’s Red Rocks Romance. Divided into three sections, it shows at its sides two kneeling men wearing the familiar dress of “cowboys:” stetson hats, jeans or work pants, western boots. The one to the left carries a bouquet of sunflowers, the other has his hat over his heart in a gesture of homage or a humble request. Between them, and somewhat larger in scale is a standing woman, wearing a fringed skirt, starred vest over a yellow blouse, western boots and a stetson. She is framed by what looks like a serrated scarlet body halo, and rays flow out beyond that forming a gloriole. Beyond all three figures is a continuous red-rock landscape, billowing cumulous clouds at the horizon and a brilliant blue sky above. Executed in acrylic on board, the whole thing is framed with a tripartite wooden frame, with a gable over the center and gilded stars and hearts.

|

| Hugo van der Goes, Monforte Altarpiece, Berlin Gemäldegalerie |

The men seem to be on bended knee perhaps adoring the lady, and that and the frame evoke medieval altarpieces, such as the one by Nardo de Cione in the National Gallery of Washington, though there, the Virgin Mary is flanked by standing saints. But the kneeling gestures of homage of two of the three kings and removed hat of Saint Joseph also recall such works as Hugo van der Goes’s Monforte Altarpiece in Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie. And of course the lady with her body halo brings back memories of the Virgen de Guadalupe. This work is basically laid out as a secular triptych.

|

| Virgen de Guadalupe |

This sort of sampling of earlier artworks is, of course, widely popular in today’s artistic and popular culture in many media. But Goettee’s work is totally in contemporary American Western Art tradition. The lady appears to my to be the ideal Western Art Woman, a Goddess of the West. The brilliant, flat coloring of the painting reminds me of billboard art, though the picture’s scale is quite small. Are the two men rivals who are courting her? Do their white and black stetsons indicate hero and villain in old western movie tradition? Or are they, as a LGBTQ colleague interprets the work, two gay cowboys whose union is being blessed by the Goddess?

Goettee, whose painting and mixed media work uses a lot of art historical and commercial art motifs, has a lot of wry humor—that same type of frame is more explicitly used in other works, Ecstasy of St. Elsie where the iconic figure is a haloed cow, or Holy Cowboy, a sort of devotional triptych having a more Renaissance-style frame with a cowboy in the center flanked by two half-length cows, one of whom is the same Elsie. His website features other imagery satirizing the mythology of the Old West.

|

| Dennis Ziemienski, Indian Detours, Booth Western Art Museum Permanent Collection, Cartersville, GA |

Indian Detours by Dennis Ziemienski is an example of another facet of Western Art: nostalgia. The scene is a tribute to tourism in the 1920s and early ‘30s. It is set in an unidentified southwestern pueblo, replete with adobe buildings, a ramada, chile ristras, and native American inhabitants in striped serapes. A touring car of Anglo-American tourists (but with a local driver) has stopped to shop from the town’s native inhabitants. Under the ramada, a lady dressed in fashionable riffs on native clothing, except for her high-heeled shoes, kneels to inspect a blue pot from a seated, serape-clad villager. Behind her, a man in a white, three-piece suit and hat fingers a rug, while two local women and a baby look on, and a third woman offers another a pot to a cloche-hatted lady within the car. Behind this grouping are two local men and a woman in a rebozo. One of the men sits on a horse (maybe an allegory of old transportation vs. new?); in scale he is far larger than anyone else. The equestrian man and the automobile form strong horizontals, echoed by the rugs. the crossbeam of the retama, and the ground. The tourists and their dress make an obvious contrast to the pueblo inhabitants, and their postures and demeanor suggest a patronizing noblesse oblige. The whites of the man’s suit, the horse and the white-shawled woman center the composition. The color palette of brick reds, tans and blues suggest the desert country of the southwest, and the canvas support, in contrast to Goettee’s work, has a matte finish.

This painting recalls one of a similar theme by Goya, one of his tapestry cartoons now in the Prado Museum. Once again the ceramics vendor is a man, who instead of sitting, reclines on a blanket. Three seated middle-class ladies examine his wares in a landscape, rather than a town scene.

Two men, possibly companions of ladies, sit on a pile of straw mats behind them, their backs to the viewer. But once again there is a division of classes, not only between the vendor and his clients, but in the aristocratic lady in a coach behind the seated and reclining foreground group. Her vehicle has four liveried outriders, reinforcing her status.

|

| Francisco de Goya, The Crockery Vendor, Madrid, Museo del Prado |

Here both the coloring and brushwork are much softer than Ziemienski’s, and the composition is based on diagonals, with the coach diagonally placed too, suggesting greater depth. The verticality of three footmen on the coach and the tower behind them, counteract all the diagonals, but there is a general sensation of lightness and action, whereas all of Ziemienski’s figures appear still and static. Goya’s painting is part of a much larger cycle of twenty tapestry designs for the Royal Family featuring “typical” scenes of country life, meant to animate an entire room. Unlike Ziemienski’s painting, this design, dated 1779, has everyone in contemporary dress, and the finished tapestry would have been in reverse, and because of the change in medium, the tapestry would have harder contours and a less vaporous atmosphere. Because these tapestries were designed for a palace, only the elite had access to this view of suburban life. Ziemienski’s painting can be viewed by a far greater cross section of viewers.

Both surely address class issues, but Ziemienski’s scene is clearly a carefully researched evocation of a time in the past—in that sense a history painting rather than a slice of contemporary life. Goettee's composition is a more contemporary icon. I wonder if Ziemienski ever saw Goya’s painting—on his biographical webpage, it is stated that he has traveled frequently to Europe—but Indian Detours is not really sampling, rather a creation or recreation maybe of a memory. On the other hand, it would make a splendid tapestry too!

_________________________________________________________________________________

Michael Goattee's Website: http://michaelgoettee.com/michaelgoettee.com

Dennis Ziemienski's website:http://ziemienski.com

Biographic Information for Ziemienski:https://www.altamiraart.com/artists/14-dennis-ziemienski/biography/