Museums can

mean and have meant many things, but I guess that the most general definition

of it in contemporary terms would be, as the Encyclopedia Britannica puts it:

“institutions that preserve and interpret the material evidence of the human

race, human activity, and the natural world.”

Many are open to public view, and can exhibit everything from art to

dinosaur bones, fire engines, famous baseball players or chocolate. One that has recently opened in Warsaw,

Poland (2013) completely blew my mind: POLIN, the Museum of the History of

Polish Jews. I made a one-day trip to

Warsaw from Berlin a couple of weeks ago (it takes less time to fly between

those cities than between Dallas and San Antonio), and spent my whole day

there. I should have gone for two and

stayed over.

The museum

is very large and beautifully designed, and totally integrated into the digital

age. It is more than just a collection

of artifacts, rather it is a journey, through digital magic, through a thousand

years of Jewish history in Poland, and the core exhibition is laid out as a

sort of directed maze through which you wander through time, with all kinds of

mixed media evoking and explaining the historical trip, and simply gathers you

in.

|

| Map of the Core Exhibition Space |

|

| Tower of San Martín, Teruel |

I first

became aware of it through an interest in vernacular architecture, especially two

regional groupings of specific types of buildings made with inexpensive

materials. In each case, the building

and certainly a lot of the architectural painted decoration was done by Muslims

or Jews, both of whom shunned human representation. The building techniques

were those of all kinds of buildings in their respective regions. One is a

group of medieval churches in Aragon, Spain, built mainly in brick and ceramics

in the 14th to 16th centuries, mostly by Muslim workmen

with local materials. Many of these

survive, and their gorgeous decorations are undergoing thoughtful

restoration. The other was a group of

wooden synagogues, built mostly in the 17th and 18th

centuries by Christian and Jewish carpenters, in present-day Poland, Lithuania and the Ukraine, likewise beautiful

and distinctive designs in wood, many of their interiors lavishly decorated

with painted wildlife, plants and words.

None of these survive. Many

simply deteriorated over time, as Jewish populations dwindled or shifted; those

that remained were destroyed during World War II—Nazi casualties along with the

populations that attended them.

Fortunately,

those that made it to 1939 were documented by Polish photographers, and in

1957, the Architects Maria and Kazimierz Piechotka published a wonderful book

of many of the surviving ones, republished as Heaven’s

Gates in English in 2003, reproducing the photographs and presenting plans and

drawings too. I was able to get the English edition a number of years ago in Krakow, and now it has been reissued

as a paperback, but so far as I know, only available at the museum. Also in 2003, an American architect, Thomas Hubka

published a superb detailed study of just one of these buildings, entitled Resplendent Synagogue, dealing with the

one at Gwozdziec.

|

| Maria and Kazimierz Piechotka |

Hubka’s text

was in inspiration. It was decided to

reconstruct the painted interior and exterior of the ceiling of the Gwozdziec

synagogue as the centerpiece of the new Warsaw Jewish museum. The job was given

to Handhouse studio in Massachusetts, under reconstruction specialists Rick and

Laura Brown, who are neither Polish nor Jewish, but quite a number of the

students from several different countries participating in the project were. There were also Polish millennials who had

never met real live Jews before. They

researched materials and construction methods, as well as the sort of paints

used in the originals. In 2013, their

ceiling as well as the gazebo-like bimah

(Torah-reading platform) was installed in the new museum as its centerpiece.

It was to

see that reconstruction that was my primary reason for making the trip, with a

secondary one that my grandfather came from Poland (Brzeziny) and had spent

time in Warsaw as well, before seeking better opportunities, first in England

and finally the U.S. The museum gave all

my grandfather’s stories that I had heard in childhood context, and helped me

understand the American Immigrant experience that shaped my parents as

well.

|

| The Old Country, 1920's: No Thanks! |

Everything

I had heard about the Old Country had sounded negative: poverty, ignorance and

prejudice. The photos I had seen of impoverished Jewish towns, or shtetls, Fiddler on the Roof not withstanding, made it seem awful. I was glad to be an American, and glad that

my grandparents had come here, beyond the fact that if they had lingered behind,

they would have been wiped out. A trip to Krakow several years back had been charming, but the pilgrimage to

Auschwitz nearby pretty much convinced me to vow never to revisit Poland or anything

Polish again. The discovery of the wooden synagogues book made me think that

maybe there was something more, and the Museum changed everything.

|

| Isidor Kaufman: Rabbi in Jablonow Synagogue |

To visit

the core exhibition, you go downstairs and enter the labyrinth, beginning in

the 14th century, when traveling Jews in the area were asked to

leave their weapons at the synagogue door before entering (so resonant

now)! Winding through tentative

beginnings—life for Jews, with no homeland to go to and no military clout was

always dicey, since they were allowed in at the whim of the places they

meandered through—into their gradual settling down both in cities and small

towns. It was a precarious journey, but they managed to survive, into a short golden age in the 17th century under the relatively permissive

Council of the Five Lands (four in Poland and one in Lithuania), when they had

some autonomy. They managed reasonably

well (except for a rampaging Cossack massacre in 1648), mostly under direct

protection of the Aristocracy, who employed them. They kept their distinctive dress, customs,

and regional jargon (later to evolve into Yiddish), and also to the professions

to which they were restricted. The

grandest of the wooden synagogues were built then, and the Gwozdziec

reconstruction takes pride of place in the museum as a symbol of that era.

|

| The Gwozdziec Reconstruction |

|

| The Gwozdziec original ceiling |

The museum

beautifully evokes those times via models, artifacts, maps and recreated sounds

(though mercifully no smells). The

visitor is channeled into ever-changing spaces, each devoted to a different

aspect of daily life and larger religious and cultural events; lighting levels,

spotlighting, and even the colors of the spaces evoking or explaining different

topics. Some rooms are large, such as

the one with a model of 17th century Krakow; some are almost niches

or nooks. Drawers can be opened,

revealing objects of significance. For

later times, there are photographs, newspapers and film footage. In each room or gallery niche, the visitor is

encouraged to look for and read texts and examine pictures and things that

suddenly bring everything to a personal level.

As the

history becomes turbulent again, through Poland’s own tragic partitions and the

waxing and waning of anti-Semitism from without and sectarian conflict from

within, the spaces wind in on themselves. Marking the beginning of the

secularism of the “Enlightenment,” they become somewhat more rectangular. With the Yiddish literary movement,

paralleling so many of the linguistic revivals of diverse ethnic European minorities at that time, I enter into more familiar territory: this was the culture of my

grandparents. Along with it came labor

movements and protests, and for the first time, prominent participation by

women. It also explains the strong

Socialist and Communist leanings of many American Jewish immigrants then (and residually,

Bernie Sanders, who is from my generation). Unsaid but always present is the

thought of where that culture might have gone if it hadn’t been so abruptly

extinguished.

|

| Alley-courtyard, Warsaw, 1920's |

|

| The Museum's street evocation |

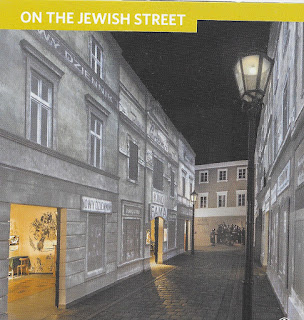

A very tall

corridor-like passage evokes a street in a Jewish neighborhood in a city: it

reminds me of a photo of one such alley in Warsaw, though it’s actually based

the prewar Zamenhofa Street, by the present museum (and a strategic place

during the Warsaw Ghetto uprising); the museum street has real cobblestones. But the light is eerie and gray, with

indistinct figures projected at the end of street, which leads into the very graphic, jagged and angular spaces of the Holocaust.Poland was particularly gruesome at this

time, since all the major death camps were located within its borders. The black ceilings seem lower here and low

lighting adds to a sense of claustrophobia. I’ve been to many other Holocaust

museums and Auschwitz too, but coming to it from the rest of this museum world,

it is particularly poignant.

The postwar

galleries are sort of anticlimactic, since there are very few Jews in Poland

now, but having this big museum in Poland is at last a tribute to what

was. Though it’s gone, there’s a

fascination there now to find this culture and treasure it s remnants by the

Poles themselves. When I was there,

there were not only foreign tourists (including a bunch of elderly Israelis

with their Hebrew-speaking guide), but large numbers of local visitors and

groups of school children. Maybe some

day real Jews might even come back.

One

postscript: the realization that up to about a century ago, women were just as

repressed here as they were in most places at that time. During the time it functioned, I would have

been banned from the glorious Gwozdiec prayer hall; women had to sit upstairs

in a narrow space relegated to them, where they could enjoy the view through a four-inch

slit cut into the wall that excluded them.

|

| Thomas Hubka's reconstructed view of the women's section in Resplendent Synagogue |

And another

Postscript: Hitler was rumored to have actually planned his own Jewish Museum

in Prague: “The Museum of an Extinct Race,” displaying confiscated Jewish

artifacts from destroyed synagogues and private homes, first from Bohemia and

Moravia, later from all over Europe, as evidence of the total destruction he

was carrying out (it did involve the survival and preservation of many of these

objects). POLIN represents a dignified and thorough tribute to what Hitler

wiped out, but affirms that Jews are hardly extinct! Ha!

____________________________________________________________

For a brief article on the diverse nature of museums see The Encyclopedia Britannica Online.

The two best books on wooden Synagogues are:

Maria and Kazimierz Piechotka, Heaven's Gates. Wooden Synagogues in the Territories of the Former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Krupski I S-KA, Krakow, 2003

Thomas C. Hubka, Resplendent Synagogue. Architecture and Worship in an eighteenth Century Polish Community, University Press of New England, Hanover, 2003.

For a briefer treatment of wooden synagogues and links online see: